By Gabrielle M. Follett.

Trust. The willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability of the ability to monitor or control that other party[1].

In a recent post in ‘From the Green Notebook’ David Beaumont noted that, for the sustainment of decisive action to be effective, logistics must be characterised by ‘trust between commanders, combat forces and logisticians’. Almost every military logistician – and no doubt the majority of our combat arms brethren – would agree.

If we accept that trust between all parties is essential to effective military logistics, why then do tactical commanders in the Australian Army generally adopt a policy of self-reliance when it comes to combat service support? At every level of the Combat Brigade supply chain – from the F Echelon through to the logistic battalion – we assume that the logistic system is almost certainly going to fail us. Moreover, as we reach back to third line logistics and beyond to the National Support Base, the decline in trust is almost proportional to the increasing geographic and C2 ‘distances’ between the elements who are supported and those supporting.

As a result, at the tactical level we deploy with a stockholding based on ‘everything we can fit in’ rather than the science of logistic planning. The repercussions are self-fulfilling: we take so much equipment and stores on our training exercises that we don’t test the logistic continuum, failing to find where it breaks and thus missing the opportunity to fix it. The lack of trust in logistic units and the supply chain is reflected in wasteful activities, hoarding of limited resources and failure to accept prudent risk. In terms of collective capability, we lose the opportunity to actually train combat and combat service support elements together, failing to build mutual understanding or respect and never affording ourselves the fortuity to be pleasantly surprised when the logistic system delivers. The result is a cultural bias that is deeply ingrained, perpetuating an often unfounded belief that our combat service support units can’t or won’t deliver what the combat arms need.

Photo by 3rd Combat Service Support Battalion, Australian Army

As logisticians, the lack of faith in the ability and skills of our logistic continuum and those of us charged with providing the support feels like enduring ‘trust deficit’. While it is generally accepted that the success or failure of combat action is dependent on a range of factors – including acceptance that the ‘enemy gets a vote’ – we approach support operations in an entirely different way. When combat operations fail, it’s because we missed information requirement X or factor Y was not available. When resupply or battlefield repair fails, it is inevitably chalked up to the perceived incompetence of the logistic unit or the inbuilt inflexibility of the system. Trust – a subjective, transactional emotion – in military logistics at the tactical level is at least partly founded on group-based stereotypes rather than heuristic experience.

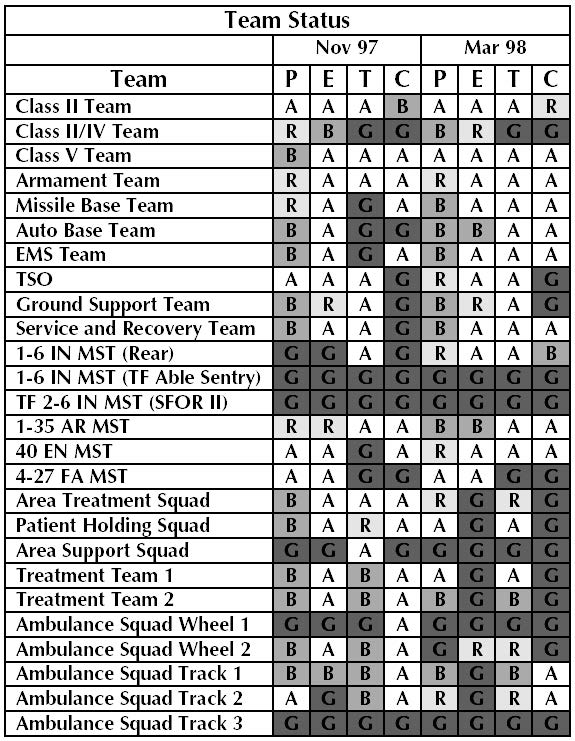

In our tactical commanders there is a clear approach of ‘trust is good, but control is better’ manifesting itself in a desire not to depend on the next level of support. This has been brought to the fore in the Australian Army’s tactical combat service support restructure[2], which in January 2017 shifted part of the combat service support personnel establishment from units into the second line logistic battalion. The premise behind the new apportionment of logistic resource is that the Army cannot afford to have all of the logistic personnel it thinks it needs, and that concentrating them at Brigade level enables prioritisation and technical efficiencies for formation operations. This disposition is analogous to how mobility support and indirect fires have been managed for decades, an arrangement that comes with apparent acceptance and trust from battle group and combat team commanders. Combat commanders are comfortable – and trust that – they will receive indirect fires when they need it and if the Brigade’s apportionment of the assets is in their favour. Yet the same command and control arrangements applied to combat service support have been met with skepticism, distrust and fear.

It is not just our combat brethren that perpetuate the expectation that the military logistic system is, more than likely, going to fail its dependencies. As logisticians in first line units we promote a lack of reliance on the next level of support. We focus on ensuring our own efforts support our unit so that we mitigate any deficiencies further up the distribution or repair chain. This facet of distrust in the system stems in part from the tribal nature of our Army. The same corps and unit identities that we develop as a component of morale and combat effectiveness lead us to distrust those who are not like us. The fact that combat service support personnel in combat units give way to a form of ‘Stockholm Syndrome’ and agree wholeheartedly that units can only depend on the logistics that they own and control means we are doing little to assuage or defeat the lack of trust in the complete logistic continuum. The same approach is perpetuated in second line logistic units, where cynicism about the reliability of third line support abounds.

Compounding our ingrained cultural skepticism is a lack of proof that our logistic system can deliver the goods. We talk of exercising our logistic systems and ‘pushing them to breaking point’. Yet in our major field training activities we prioritise objectives more tangibly linked with joint land combat at the expense of actually testing our combat service support. Instead of considering the ‘four Ds’[3] during exercise design, we can rarely afford the funding to position our third line logistics at the distance needed to generate realistic lines of communication, meaning that the force support and brigade support elements end up in close proximity to each other. The exercise duration– driven by concern about how long we are away from home locations – is short and finite, inevitably supporting a self-sufficient approach. Our ‘destinations’ are well known to us through the geography of well-trodden training areas, meanwhile ‘demand’ is shaped by the finite nature of the activity and set training objectives. But it’s a false economy; the fact is the cost of not training with realistic lines of supply, reasonable demand and extended duration will be felt when Australia is next required to lead an expeditionary multinational force in our region. What we don’t learn now in training will be painfully apparent on operations when the consequences are much higher.

Photo by 3rd Combat Service Support Battalion, Australian Army

Trust is a belief in the reliability or ability of something and is the measure of the quality of a relationship. We work hard at unit and formation levels to build these relationships, training and planning together. Within a combat brigade, the relationships between commanding officers are almost universally very strong. As a logistic battalion commander, I often receive emails and calls from peers who tell me how professional and capable my soldiers are. Some of these calls carry a genuine (and perhaps concerning) tone of surprise, but all of them speak to the understanding that these commanders have of the importance of logistics. Likewise, our senior leaders frequently highlight how, as they become more senior, they increasingly spend more time focusing on logistics. Yet despite this leadership, emphasis and quality of relationships between commanders, our organisational belief in the reliability and ability of the logistic continuum remains low.

Why haven’t we built this trust? Firstly, trust must be based on demonstrated competence. As previously noted, we aren’t generating collective opportunities that enable combat service support units to demonstrate competence, or to quantifiably expose the shortfalls so we can win resources to fix them. This requires more than simply limiting what each unit deploys with on – it necessitates acceptance that if we do expose logistic shortfalls they may degrade or prevent the achievement of combat arms training objectives. While we collectively believe that our logistic resources are inadequate, we do not have the organisational maturity to accept that training to expose such shortfalls may be necessary to prove the requirement for resources to fix it.

At an individual level, we wait too long to teach our junior commanders that combat service support is a crucial part of the combined arms team, equal to the other components. The Australian Army Logistic Officers Intermediate Course and Combat Officers Advanced Course come together for a short period to conduct a staff planning activity. Although badged as combined training, the lead up lessons remain separate, the problem sets are not actually constrained by logistic culminating points and the simulation system does not consume logistic effort beyond a rudimentary level. Without a mature individual training framework that treats the combat and logistic elements of the problem equally, our combat arms officers walk away with the perception that logistics is a sideshow of limited consequence.

To address the trust deficit we would do well to note that the United Kingdom’s doctrine lists the first principle of logistics as ‘collective responsibility’[4]. As logisticians, the onus is on us to communicate the imperative and the risks and to create opportunities to show what combat service support elements can actually do. We must recognise that trust is reciprocal, transactional and based on demonstrated competence. We have to get past our own arrogance and believe that when a battle group demands for something at short notice, they have good reason for doing so. We are as guilty of distrusting our dependencies as they are of distrusting us. As the supporting arm, combat service support units must accept that inevitably and rightly, the dependency defines success.

Our collective challenge is to build trust in unpredictable environments, where we are part of a continuum in which we are not always the number one priority and definitely aren’t pulling all of the levers. Transparent honesty is essential to build trust so that when we truly do require lead times or genuinely can’t meet a requirement, our relationship with our dependencies is robust enough to accept that some things truly aren’t possible. Trust must be earned and earned quickly, as the cost of not demonstrating competence or exposing logistic capability shortfalls so they can be addressed could, without exaggeration, be counted in lives.

Gabrielle Follett is an Australian Army officer and a current logistic battalion commander in the 3rd Brigade. She has served in command appointments and staff appointments at formation and force level, as an instructor at the Royal Military College – Duntroon, and at the strategic level in Army Headquarters and Australian Defence Headquarters. She has operational experience as a combat service support team commander, operations officer, Joint Task Force J5, and as a task group S4 in Tarin Kot, Afghanistan.

Follow us at Twitter: @logisticsinwar and Facebook : @logisticsinwar. Share to grow the network and continue the discussion.

[1] Mayer, R.C., Davis, J.H., Schooman, F.D. An integrative model of organisational trust, The Academy of Management Review Vol 20, No 3 (July), 1995, pp 709-734

[2] Known as the ‘Combat Service Support Concept of Operations’ or ‘CSS CONOPs’.

[3] Australian land warfare doctrine describes logistic planning factors known as the ‘four Ds’ – destination, demand, distance and duration. Developing doctrine expands this to ‘five Ds’ with the addition of ‘dependency’.

[4] UK Army Doctrine Publication Land Operations, Chapter 10 – Sustaining Operations